I don’t want to talk about home, too

I remember the first time I saw the title of this book on my friend’s Instagram story. She doesn’t want to talk about home? I was taken aback. How could she not? Home is all I ever talk about. It’s my whole identity. My American classmate once joked that I could never shut up about Syria. I laughed so much as she wasn’t wrong.

Since leaving Syria in 2021, home has become everything to me. I wanted the world to know what was happening there. I wanted to help. The guilt was unbearable. I volunteered, and I created my own digital platform to ensure I never lost my connection to working for Syrians, with Syrians.

Then, I arrived in the UK and became an asylum seeker. Once again, I sought out ways to work with displaced people, to serve them, and to make sure they never felt what I was feeling. Lost, incompetent, unwelcome.

During an office hour meeting with one of my lecturers, we discussed my assignment on Syrian students at the Universities of Sanctuary. He liked the idea and how passionate I was about it. When we were finishing, he paused and asked me:

“Are you doing this because you want to? Or because you have to?”

I hesitated before answering. Both.

I want to talk about us. And I have to. I was privileged enough to escape, so I feel responsible to keep speaking, researching, and working.

He nodded. “I understand. Just make sure you’re alright.”

I didn’t fully get what he meant at the time, but his words stayed with me.

That first semester, I dedicated every assignment to home, examining Syria from different angles. I read data, papers, and reports. I saw the war through a detached, analytical eye. And that broke me more than I realised.

I remember talking to my therapist when I was living in Istanbul. After I finished updating him on my life, he asked:

“Loujain, you lived through 10 years of war in Syria, right?”

“Yes.”

“Then what you’re experiencing are PTSD symptoms.”

I froze. I had read about PTSD. Deep down, I always knew I had it. But hearing it spoken aloud made it real.

“It’s a fresh wound,” he said. “You need to cut yourself some slack.”

When my friend visited Syria for the first time in 20 years, she returned with an observation: “I love it there, Loujain, but everyone seems to be fighting for something. They are very competitive.”

I’ve always taken pride in being the hardworking girl, the fighter. That fight-or-flight instinct is second nature to me. It had to be. In Syria, nothing is fair. If I didn’t fight for what I wanted, it would pass me by, even if I deserved it. I had to fight to be seen, to be heard, to be respected.

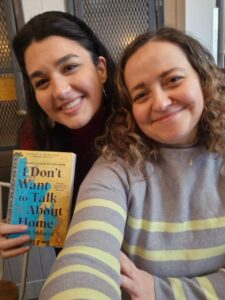

Reading this memoir felt like closure after 13 years of war. It was as if someone had written my story, everything I had ever wanted to say about Syria, the good and the bad. I no longer feel the burden of constantly needing to talk about it.

It was like tearing off an old bandage, exposing wounds I had ignored for too long. It gave me space to breathe and the permission to revisit my past with compassion instead of guilt.

For the first time, I truly understood what my professor meant when he said, “Make sure you’re alright.” I never realised how much reopening these wounds was hurting me. How it was trapping me in one dimension of my identity. “Loujain, from Syria” the one sentence I used to address myself with, thinking that being the Syrian girl was big enough to fit me.

But I’m not just that.

I’ve spent years being resilient, and I’ve been praised for it. You survived the war, you can survive anything. But I don’t want to be that girl anymore. I don’t want resilience. I want ease. I want softness. I want peace. I’m tired of fighting. I’m done fighting.

Returning from winter break, I felt relieved that no one was asking me about home. No “What’s happening there now?” No “How is everyone?” No “Are you afraid of what’s coming?” No “Are you you thinking of going back?”

I didn’t know. And I didn’t want to know.

I even avoided the only Palestinian girl I know in town because I knew she had questions I had no answers to. I was exhausted from being the girl with the tragedy. It’s a burden that I don’t want to carry anymore. I want to break free.

Then, at a Chinese New Year event, I ran into a university staff member who had always been kind and always checked in on me. After the usual small talk, she casually said:

“You should be grateful your family is in Syria and not in Gaza.”

I froze. I didn’t know what to say. So I said nothing. I walked away, distracting myself with the celebrations.

But her words got under my skin

I returned home thinking I should be grateful?

Grateful for being displaced? For not seeing my family for two years? For missing every occasion, every gathering, every moment? For spending Christmas alone while everyone else is surrounded by love?

No. I’m not grateful, madam.

I’m full of rage, anger, sadness, disappointment.

I’m feeling home-less, abandoned, unattached, left out with no social support.

Does this sound ungrateful to you?

It seems you can’t receive compassion without pettiness. You can’t get sympathy without humiliation. It’s all packaged together, and I’m sick of it.

The next day, I put on the Syrian map necklace -I had ordered weeks ago but never felt like wearing- to her workshop. I don’t know why I did it. Was I trying to reclaim something? Was I reminding myself that I’m not ashamed?

I don’t know. I just know I’m tired.

Being Syrian comes at a cost I’m no longer willing to pay.

It had been so long since I finished a book in three days. When I closed this one, I closed my eyes and cried for what felt like years.

I cried it all out. I cried the war, the stress, the anger, the fear, and the loneliness. The longingness. The dark, cold nights, the bombshell sounds, the nightmares, the endless goodbyes, the friends I lost, the bureaucracy, the waiting lines, the instability, the dead bodies, the languages I never understood, the racism, the never spoken memories. I cried every version of me that lived in three different countries.

I cried for the home that is no longer home.

And I finally let myself grieve home.

Loujain, you are displaced. You are now as the quote says:

“So, here you are

too foreign for home

too foreign for here.

Never enough for both.”

I don’t think I’ll ever be home again. And that’s why I don’t want to talk about home, too.

لجين,

مدونتك تصف التطور الأخلاقي لكل سوري يعاني من “ترف أن أكون وحيداً”

شكراً لك

كتير حلوة

Quite eloquent and heart warming.

كتير حلوة

احسنت لجين